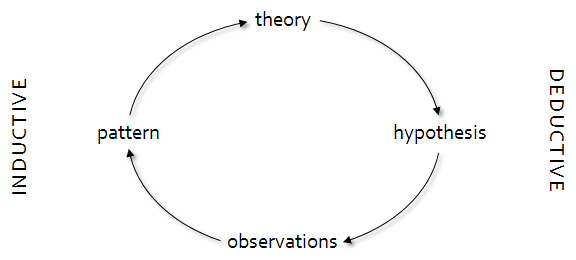

Last year I went looking for an “inductive-deductive loop” image (I was trying to convince stone-cold scientific method biologists that it really is okay to start science from observations), but I couldn’t find anything close to the simple diagram I was envisioning. So, I drew my version on a Post-it note, and I’m sharing it now for posterity and for Google Images.

My talking point here is that scientific inquiry is both inductive and deductive. Although many disciplines privilege a single type of reasoning, it’s better to integrate both approaches. With a circular view, we are free to enter problems where it’s most straightforward to start them — exploring the data, taking hypotheses or patterns to their conclusions, or considering how known theories might manifest — knowing that we’ll do a complete investigation in the end. We trace as far as we can through the loop, verifying our interpretations through multiple methods. Sometimes we cycle around the loop multiple times.

For instance, if you’re heavy on data and light on abstractions, you might start by trying to find patterns in the observations. Once you identify some patterns, you formalize those patterns into a theory. Given theory, you can generate some hypotheses based on the implications of that theory. You then collect more data to disprove those hypotheses. The new observations might suggest new patterns, starting another round of the loop. You don’t limit yourself to collecting data only to disprove hypotheses, though — you also look at data that hasn’t been deliberately collected under the premises required by your hypotheses. By looking at all the observations, you can start to investigate when the premises themselves hold.

The inductive-deductive loop is the structure of scientific inquiry.